PennyLynn Webb | Jul 16, 2019

Gov. Greg Abbott has made the second Saturday in September Quanah Parker Day.

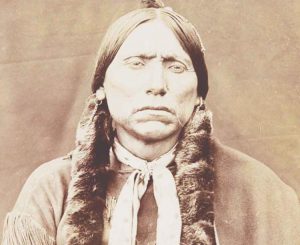

Quanah Parker, the son of Cynthia Ann Parker and Comanche Chief Peta Nocona, is an iconic historical figure. He was the last great chief of the Comanche people during the difficult transition from free ranging life to life on the reservation.

He was an influential negotiator with government agents, a prosperous cattle-rancher, and a vocal advocate of formal education for Native American children.

The bill, signed by Abbott on Jun 10, was sponsored by Justin Holland, a Texas representative from Rockwall.

“This will mean that it’ll be..promoted with schoolchildren,” said Ron Parker, Quanah’s great grandson. “Children will know about that day.”

One of the reasons for the honor, is Quanah has been identified as a founder of the official state bison herd of Texas at Caprock Canyons State Park. This free-ranging bison herd are the very last bison of the great Texas southern plains bisons herd.

Quanah is also a Texas historical figure with strong ties to Houston and Anderson counties and many families who live here today.

It started with John Parker’s son, Daniel. In 1832, Daniel Parker, a staunch theologian, received permission to settle in Texas. He organized a group of people as part of the Predestination Baptist Church. They left Illinois in July of 1833 in an ox-drawn wagon.

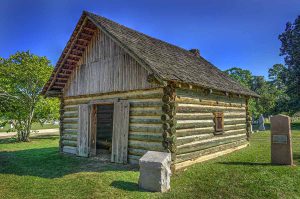

Daniel and the majority of his followers originally settled in Grimes County but later moved to near present-day Elkhart, where a replica of their Pilgrim Baptist Church stands. Other group members went farther west, near the Navasota River and present-day Groesbeck.

Elder John Parker and three of his sons, Silas, James and Benjamin, cleared land in December of 1833 for the construction of “Parker’s Fort.”

John Parker negotiated treaties with local Indians, who were subject to the Comanche. Historians believe Parker thought the treaties applied to all Indians and would protect his family from any attack.

Comanche customs, however, regarding treaties made by subject tribes didn’t limit the Comanche as a raiding nation. When Comanche raiding season began, Fort Parker was one of many settlements subject to attack.

It was on May 19, 1836, when the Comanche Indians attacked the fort. The Comanche killed five settlers and captured another five, as 21 surviving settlers fled to what is now Palestine.

Cynthia Ann Parker remains the most famous of those Comanche captives. The Native Americans caught John Parker and his men in the open. They managed to fight a rear guard action for some of the escaping women and children, but soon they too retreated into the fort. The Indians attacked the fort and quickly overpowered and outnumbered defenders.

They killed John Parker, but took two of his grandchildren and three others alive.

Historical accounts state that Cynthia watched as the attackers raped other women, and the men tortured and killed the other residents. John Parker was the last to die. He was brutally tortured, scalped and then killed.

The five captives, including -year-old, blonde-hair, blue-eyed Cynthia Ann, the daughter of Silas M. Parker and her brother John Richard Parker whom the Indians led away into Comanche territory.

A rescue party formed to save the captives. During their pursuit of the Indians, a teenage girl escaped.. The others were eventually released in exchange for ransom. However, Cynthia remained with the Comanche for nearly 25 years.

John Richard Parker was ransomed back to his family after six years, but was unable to adapt to white society and returned to the Comanche.

Cynthia Ann received the name Nadua that translates as “Someone Found.” She was adopted in the Nocona band of the Comanche. Although she was beaten and abused at first, Cynthia Ann adopted to Indian ways and later married Chief Peta Nocona, with whom she had three children: Quanah, Peanuts (sometimes referred to as Pecos) and Topsana, which translates to “Prairie Flower.”

As a tribute to Nocona’s great affection to Cynthia, he never took another wife, although it was traditional for chieftains to do so.

In December of 1860, Cynthia Ann, 34, and Topsana were captured in the battle of Pease River. They were reunited with Cynthia’s white family. However, Cynthia did not want to stay and is said to have mourned, even running away once, wishing to return to her Comanche family and her sons. Topsana died of an illness in 1863. Heartbroken, Cynthia, stopped eating and died of influenza in Anderson County in 1870.

Several years after the Pease River battle and after the death of Nocona, Quanah was taken under the wing of Chief Wild Horse who taught him the ways of the Comanche warrior. History states that Quanah received considerable honor as a warrior and joined the Quahadi Comanche band, which grew to become the largest and most notorious of the Comanche. Quanah became the leader among the Quahadi Comanche and led the tribe successfully for many years.

After the Comanche tribes on the “Staked Plains” were defeated, Quanah led his group to surrender to the authorities after the battle of the Great Plains. Their food sources were depleted and they were under constant pressure from the army. They were forced to live on a reservation in Oklahoma territory.

The Quahadis were the very last tribe on the Staked Plains. Quanah was made the chief of all the Comanche tribes on the reservation, and proved to be a forceful and resourceful leader. Through investments, he became very wealthy.

After moving to the reservation, Quanah reached out to his white relatives from his mother’s family. Many of them rejected him at first. However, after much correspondence, they began to connect. He even visited the Anderson and Houston County area, staying with relatives for a few weeks to study the English and Western culture and eventually adopted the surname Parker.

Quanah forged a close relationship with several Texas cattlemen, like Charles Goodnight and the Burnett family. He worked with these men to build his own herds. He also worked to see that the tribe received “grass” payments for grazing rights on Comanche, Kiowa and Apache lands.

Quanah passed away on Feb. 23, 1911 at the age of 59 at his home, Star House, on the Comanche reservation. Before his death, he arranged for his mother and sister to be reburied in a plot next to his own at Post Oak Cemetery near Cache, Oklahoma. In 1957, due to an expansion of a missile base, the three were moved to the Fort Sill Military Cemetery in Oklahoma.

Old Fort Parker was reconstructed to pay tribute to the Parker family and the other pioneer families who journeyed to Texas from Crawford County, Illinois in 1833.

For directions to the Old pilgrim church, click here.

See the original article by the Palestine Herald Press at: https://www.palestineherald.com/news/historical-figure-with-local-ties-gets-annual-holiday/article_de27b862-a832-11e9-ae03-efd438739365.html#tncms-source=article-nav-prev